In a world where people draw distinctions between saints and sinners, she realizes they can be one and the same.

Cate MacQueen can’t sleep. She carries with her 10 ink-laden notebook pages of notes, a pocket picture purse filled with images of her sons and, it seems, the weight of the world.

It’s been like this — or a version of it — since Cate’s son Casey, known in newspaper headlines as Benjamin MacQueen, died in a head-on car crash on March 11 near Kingston.

The truth is, her agony stretches back more than a decade, even before her son found himself in a desperate struggle with heroin.

“As a parent that’s automatic: ‘Could I have done this? Could I have done that?’” Cate asks rhetorically. “No parent thinks their kid will do this. A lot of parents, I think, put their head in the sand.

“The only thing I can think of is that I didn’t come on strong early enough. The last three years, I held nothing back. I let him know that I knew.”

Cate’s pain stretches at least as far back as the day her son Adam, Casey’s brother, was involved in an automobile wreck that nearly killed him and caused lifelong, disabling injuries — and in the process, changed their family’s life forever.

Born in Los Angeles, Calif., on Nov. 15, 1986, and raised in Arizona towns Lake Havasu City and Chandler, Casey Benjamin Ybarra and his older brother Adam were, as their mother sees it, particularly active youths.

“Casey was such a wonderful kid: intense, creative, sweet, resourceful, self-sufficient; he was the total kid-next-door,” Cate says. “Anything he tried, it was easy for him.”

Hard-working and industrious at an early age, Casey was active in Boy Scouts and soccer teams, paying the cello at a young age, BMX racing and working on cars. “They were busy, non-stop busy,” Cate says of her boys.

By the time he was in high school Casey had a job working for the school’s information technology department, kick-starting a lifelong interest in computers.

But in 2004, the first of three major car wrecks changed the family’s lives forever. In his senior year in high school, Adam — 19 at the time — left his house in the early evening to pick up his friend at work, which was less than 20 minutes away. Later that evening, Casey, 18, got a call wondering where his brother was. Casey retraced Adam’s route and came upon emergency crews responded to the scene of a car crash, with Adam’s vehicle wrapped around a tree. Cate recalls that someone told Casey the driver had been airlifted to a nearby trauma unit.

Cate was without her cellphone and is four hours away, so for the next 10 hours Casey was on his own while surgeons, doctors and nurses worked to save Adam’s life. Adam was on respirators unable to breathe on his own. His neck was broken in two places, his diaphragm had completely ruptured, his hips were broken, his lungs were punctured, he had lost ribs, and doctors believed that he might be paralyzed.

(Cate finds out later that Adam was speeding through a long stretch of a residential area on a curvy road with a large, raised island in the middle to divide traffic. A rear tire blew, sending his car bouncing off the divider, up on an embankment and wrapping itself around a tree. “Initially there were charges of reckless driving, etc., but because of the nature of Adam’s injuries and his permanent disability as a result, all charges were dropped,” Cate says.)

Adam, in a coma for six weeks and in lengthy physical rehabilitation for weeks thereafter, had to relearn to walk and talk. Adam, who lives with Cate to this day, was left permanently mentally disabled, she says.

The wreck took its toll on everyone in the house. Casey, whom Cate affectionately calls a “mama’s boy,” quit his job to stay home and help feed, clothe — and if, needed, bathe — his brother as Adam recovered.

“Casey gave up everything for us at that time,” Cate says. “We were all three changed forever and Casey would always say that he lost the brother he once knew in that accident.”

(By that time, Cate says, the boys’ biological father, Steven Ybarra, had not been in the picture for several years.)

Being homebound, both boys earned GEDs for their high school diplomas.

“(Casey) just dropped everything to help me,” Cate says, “(but) he really mourned and grieved over his brother.”

It was near that time, Cate says, when Casey, then 17, began battling serious depression … and to experiment with hard drugs. Initially, she says, it was marijuana — a so-called “gateway drug” — that piqued his interest. It progressed to methamphetamine and eventually to heroin, Cate says.

“I still don’t understand what goes through the head of a heroin user,” she says.

‘I’m fine mom. I’m fine. I can handle this. I got it.’

Cate MacQueen has heard this before from her son. It and other variations are common phrases that echo from the lips of addicts to the people they love, she says. In Casey’s case, it echoes from the grave.

“He was a kid who got stuck on something he couldn’t let go of,” Cate says. “He kept trying to stop.”

Cate moved herself and Adam to the Sequim area about eight years ago, while Casey continued his battle with drugs in Arizona. He was caught for possession and intent to sell marijuana, Cate says, and wound up serving time. She carries a reminder of that time: an envelope that contained a letter from Casey as he served his sentence. The worn and folded paper shows a penciled cartoon drawing Casey drew on the outside, the work of a young man with a boyish imagination.

Casey served a little more than two years.

As it was, Casey was open about his drug use and his mom was the supporting and sympathetic ear. But looking back, Cate says she wishes she had been more vigilant about helping her son try to break his addiction.

“He was very functional — I never heard anything but great things from employers,” Cate says. “He was always well-groomed … very professional, sociable. To see him you wouldn’t know it. As his mother, I could tell he was (using). He was too run down.”

As years passed, Casey found his arrest conviction made it tough for him to find work. When you Google his name, the first thing that pops up is a mug shot and information about his arrest and booking in Maricopa County, Ariz.

Three years ago, Cate asked her son to move to the peninsula. “Keep him close” was the idea. Firm but undeniable love would help him beat the addiction.

“I just wanted him to know that I know,” Cate says, “that, ‘I love you unconditionally’ and ‘I won’t leave you’ and ‘I’ll get you the help you need.’ That was always my attitude.”

“He served the time and paid the fines and fees (but) he could not move forward,” she says.

To help gain some distance from the past, Casey took up his middle name for his first. Cate, who now works in the human resources department at 7 Cedars Resort, says Casey began his own freelance computer business, helping customers with diagnostics and repairs. He had a girlfriend and got an apartment in Port Angeles. He was starting to build back a life, his mom says. But he couldn’t shake the heroin.

“He’d been telling me he was using heroin off and on,” Cate recalls. “He told me after a while, ‘You’re not trying to get high. You’re trying to not be sick, to not withdraw.’ I’ve seen him in withdrawal. It’s the most horrific thing. It’s days and days. They call it being ‘dope-sick.’”

July 1, 2014: In the second in a trilogy of car crashes to change his life for good, Casey’s car crossed the centerline of U.S. Highway 101 near Discovery Bay and Diamond Point, striking a semi, according to a Washington State Patrol report.

According to that report, Casey was flown to Harborview Medical Center with serious injuries and was later cited for drunken driving and driving on a suspended license.

Among his injuries were a jaw that needed to be rebuilt with wire and metal plates, a severe hand injury and a torn aorta, Cate recalls.

Disturbingly, she notes, Casey’s injuries may have been less severe had he not insisted — as he had for years — on not wearing a seat belt. He felt, she says, that since it did his brother no good to have a seat belt in the crash 10 years earlier, the thought was, “’Why wear one?’”

The wreck left Casey in constant pain. He and Cate worked with doctors to find a balance between mitigating his pain and fueling his drug addiction.

“They tried treating him with methadone,” Cate says. “It was hard to find a good vein because he was using at the time.”

Over the better part of a year, Casey tried to rebuild his life. But this second major crash, him mother believes, sent Casey further into depression.

“He can’t drive,” she says. “He feels like he’s getting buried. He feels like he’s going under. He could never make a normal life for himself. With all the success in his life, Casey found it very difficult to separate his behavior as an addict with the beautiful human being he was and continues to be in my heart. As they say, this made him his very worst enemy … along with the help of those substances that helped him to forget. Casey would never come to forgive himself, his behavior, and most importantly how it affected his family and those closest to him. “This ferocious cycle is what takes so many of our young people,” Cate says.

The way his mother sees it, Casey was making some progress. Though Casey had two court cases coming up, he was looking into taking part in Clallam County’s drug court program.

“We just didn’t make it that far, which is the saddest thing,” Cate says.

It’s like these people who think they’re expert wild animal trainers. People think they can tame them. But they can’t.

Cate MacQueen doesn’t care for cars much anymore. She gets around, sure, but her greatest fear — that yet another car wreck will take her life — will leave her son Adam alone in the world. In the past month, Adam’s problems with seizures has worsened.

Cate’s is both a lonely pain and a shared one. On one hand, she knows that people only know of her son from headlines in newspapers and the Internet, that his identity will forever be linked with drugs and car wrecks.

Fair or not, those facts create division between her and others who want to judge her and the family for what supposedly she did and did not do as a parent.

“Addiction and these tragic events can happen to any family,” she says. “The many, many young people under the influence of one thing or another are not just about the drug addiction. They are quite often about so much more.”

Yet, by happenstance, she is joined by a growing number of grieving parents, siblings, friends, co-workers and acquaintances who feel the impact of losing a loved one to drugs.

“I still can’t believe he’s not going to walk through that door,” Cate says.

It’s unfortunate company for sure, but Cate says she’s finding there are lessons to be learned and some comfort to find.

“Casey, he was so good at keeping it hidden, but you can only go so long,” she says. “(Drug users) are like the wild animal trainers. The beast, of course, is the drugs. No conscience, no guilt. They just do what they do. They kill and they hurt people and they destroy families.”

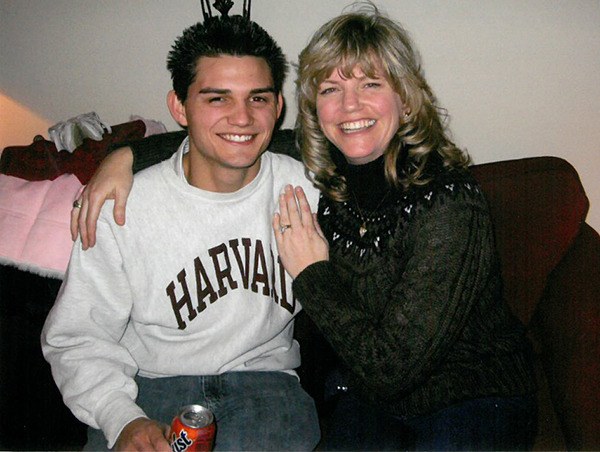

The pictures she carries, ones of Casey and Adam at various ages, are a kaleidoscope of boys becoming men. They find Casey sharing a couch with his mom, embracing his girlfriend, hanging tightly to his brother, standing alone. In almost each one, he is grinning.

None of them shows a hint of an addiction — yet it is there, somewhere inside.

“He felt a lot of shame over not being able to battle this successfully,” Cate says. “(Casey) was such a strong-minded, strong-willed person in every other way. It was just a demon to him.”

That realization fuels Cate MacQueen to seek out parents of young adults, hoping Casey’s story can serve as a lesson. She’s working with the Washington State Department of Transportation to secure the section of state Highway 104 where Casey died for the Adopt-a-Highway program.

“I am excited for the contribution I can make to the community on Casey’s behalf,” she says. “There will a be sign post placed thereabouts as soon as I get started. I will chose a brief ‘In memory of … ‘ statement for the (highway) sign. I am thinking about doing the same at his original crash site at Diamond Point as well.”

She carries her son’s memory with her into conversations with parents of teens and young adults, hoping they can recognize the warning signs.

“Open your eyes, pay attention,” Cate says. “I don’t want any more young people dying … or hurting someone else.”

On March 11, 2015, the 28-year-old man police reports identify as Benjamin MacQueen drives off the Edmonds-Kingston ferry and, headed westbound, approaches the intersection of Highway 104 and Parcell Road at about 7:45 p.m.

His car, a 1994 Toyota Camry, crosses the centerline. It strikes a 1994 Jeep Cherokee with two persons inside. James Norberg, 53, of Kingston, and his 14-year-old daughter are injured in the crash. North Kitsap Fire & Rescue use hydraulic extrication equipment to free the two and they are flown to Seattle’s Harborview Medical Center for treatment. A few days later, a Harborview spokesman notes, the daughter is discharged and Norberg is reported in satisfactory condition and out of the Intensive Care Unit.

MacQueen dies at the scene. The Kitsap Coroner’s Office lists cause of death as blunt force trauma.

“There’s a peace I’ve gained from knowing he’s not in pain,” Cate says. “I watched him hurt for so long. He felt just horrible about himself. He’s not suffering. That brings some peace, that he’s not hurting anymore.”

None involved in the March 11 crash were wearing seat belts. Marsha Masters, target zero manager for the county’s Traffic Safety Task Force, told the North Kitsap Herald that she was shocked when she read the State Patrol statement that nobody in the crash was wearing a seat belt. She noted that seat belts may not have prevented MacQueen’s death or minimized injuries to the man and girl, but that it is a common-sense safety precaution.

“It’s just that, who knows if they would have been as serious?” Masters said.

A State Patrol trooper says there was potential for drugs or alcohol being involved in the crash, but that the cause won’t be known until after an autopsy and toxicology are completed.

Cate is waiting for the toxicology results. She says she’s been told they may not come until 10 weeks after the samples are sent for testing, or around May 22.

Casey was returning from Seattle. She says she doesn’t know why he was there, nor if he was using drugs that day. She knows what the State Patrol report says, but believes either way that drugs — heroin in particular — had a hand in her son’s death.

“I’m not sure I’ll be surprised either way,” she says.

“I thank God daily for the past three years that Adam and I have had with him, being close to him. But no matter how close I was to him, I still could not get to him fast enough.”

Reach Gazette editor Michael Dashiell at editor@sequimgazette.com.