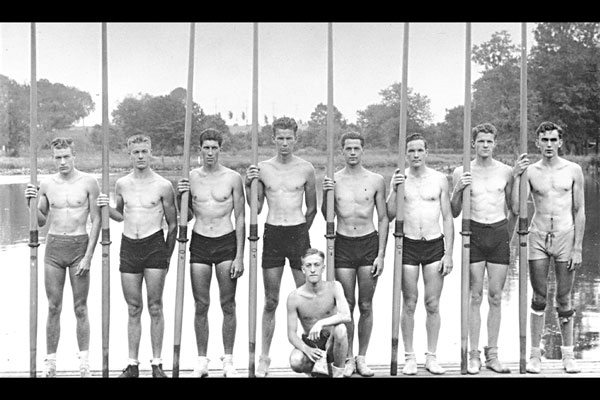

Fate took the late Joe Rantz from heartache to glory and from the small town of Sequim to the medal stand in Berlin. A new book tells the tale of Rantz and his gold-medal-winning teammates on the 1936 eight-man U.W. crew team.

On a team of unlikely sports heroes, Joe Rantz was the epitome of an underdog.

Abandoned by his family to fend for himself while just a boy, Rantz left the small town of Sequim in his teens and in just a few years found himself upon the world stage — rowing for glory, gold and the pride of a nation.

Sound like perfect ingredients for a novel? A movie, perhaps? Yes, and yes.

Such is the fodder for Daniel James Brown’s “The Boys in the Boat: Nine Americans and Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics,” released last week to the delight of University of Washington alumni and Northwest rowing fans alike.

The inspiration and spotlight falls predominantly on Rantz, who overcame a rough start in life to help that U.W. squad to gold, then went on to a successful professional career as a chemical engineer at Boeing.

The Huskies’ victory in Berlin was hardly expected; without the pedigree of Ivy League schools, Washington earned an improbable win in the collegiate national championships to earn a spot at the Olympic Games.

In the following days, the team had to literally pass hats throughout Seattle to collect enough money for travel and expenses to Germany’s Games.

Then came a come-from-behind win in the 1936 eight-man crew finals as the Americans edged Italy by six-tenths of a second, 6:25.4 to 6:26. It was a performance legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice called the “high spot” of those Games.

Rantz died in September of 2007 at the age of 93, but not before a serendipitous meeting with a neighbor that led to “The Boys in the Boat.”

‘It mesmerized me’

Joe Rantz’s daughter, Judy Willman, had a special source for a book she was reading to her father in his final weeks in hospice care six years ago: Brown, a neighbor, had penned “Under a Flaming Sky,” about a firestorm in Hinckley, Minn., in 1894.

Willman asked Rantz if he’d like to meet the book’s author. “All I knew about Joe,” Brown recalled last week at a book signing in Seattle, “was that he rowed in an Olympic race. Over the next hour Joe began to spin a tale … it mesmerized me.”

As Rantz filled in the details of the screenplay-worthy twists and turns of plot — U.W.’s world record-setting preliminary race, the Americans’ poor lane placement in the finals designed to give Germany and Italy an advantage, the Americans’ last-place standing halfway through that final, the furious charge that gave Rantz and company gold — Brown knew he had something more than an anecdote to pass along in conversation. Others needed to know this story.

It wasn’t so much the championship race that entranced Brown, but rather the humble beginnings of Rantz and the eight others on the team — oarsmen Don Hume, George Hunt, Jim McMillan, Johnny White, Gordon Adam, Charles Day, Roger Morris and coxswain Bob Moch — and the generation they represent.

“One of my motives for writing this book is to honor all of them,” Brown said.

“As Joe finished,” Brown recalled, “I asked if I could write a book about it.”

Rantz agreed, but only if the book were about the whole crew. Brown agreed to the request. Now, Willman said, the story has taken on a life of its own, with a full-length feature film in the works. The Weinstein Company (“The King’s Speech,” “Inglourious Basterds,” “The Artist”) bought the rights in March 2011.

“We didn’t know where this was going (at the start),” Willman said. On June 4, she joined Brown at the University of Washington Bookstore as he kicked off a book tour for “Boys in the Boat.”

“Being on the crew changed how he viewed life,” Willman told a rapt audience in the bookstore last week. “It wasn’t (winning) the gold medal.”

A troubled start

Born March 31, 1914 in Spokane, Joe Rantz lost his mother at the age of 3. His father, Harry, unable to cope with his wife’s death, fled for the wilds of Canada after sending Joe east to Pennsylvania to live with his aunt. When Joe was 5 his older brother Fred graduated from college, married and brought Joe to Idaho to live with him.

When Joe was 7, Harry returned from Canada, built a house in Spokane, married, and sent for Joe. But life as a family was short lived and Joe was mostly sent to live elsewhere – often having to work for his keep – as Thula, Joe’s stepmother, repeatedly refused to allow Joe to live with them.

In 1925 the family moved to Sequim. Harry had purchased the Sequim Tire shop and Joe was brought back to live with the family in the apartment above the shop. There was a sort of uneasy truce for several years, and then in 1929 Thula declared to Harry that she was leaving with her own children, that Harry could come with her or not, but Joe was not to come. So Harry left with Thula and Joe’s four half-siblings, leaving Joe to fend for himself.

Joe Rantz was 15.

It wouldn’t have turned out so well, Rantz recalled in a 2006 interview, without the help of the McDonald family, who lived on adjacent land and kindly took him in for meals and get-togethers. Rantz did what he could to make ends meet: cutting down cottonwoods along the Dungeness to sell at the Port Angeles pulp mill, pulling salmon out of the same river to supplement what food he could get at friends’ houses and playing various musical instruments to entertain and make a buck.

By his senior year, Rantz was hoping to attend college. His brother Fred, a teacher at Seattle’s Roosevelt High School, said no university would look at Rantz if he had a diploma from Sequim — there was a question, Willman said, of whether Sequim High would be accredited the following year — so the big brother convinced Rantz to move in with him.

One day, University of Washington crew coach Al Ulbrickson wandered through Roosevelt High looking for strong young recruits for the University of Washington’s freshman team. He spotted the 6-foot 3-inch Rantz on the school’s gymnasium high bar, then went to the nearest classroom and asked the teacher if he knew the young gymnast.

“Yes, I do,” said the teacher. “That’s my brother.”

Needing money to get his university career started, Rantz took 15 months off after high school graduation in 1933 to work Sequim’s hay fields. While he was there, Rantz took a job paving the then gravel-only highway between Sequim and Port Angeles. It was backbreaking work, but it paid off later on.

In 1934, UW’s eight-man freshman crew was so good that Ulbrickson promoted the whole team in 1935.

In races, Rantz’s teams had one clear characteristic: They were a come-from-behind team. In the collegiate four-mile races, they simply got stronger as the race wore on while others didn’t. Rantz and company never lost a collegiate race.

At the USA Olympic trials, UW’s Huskies pulled away from runner-up University of Pennsylvania, earning the right to represent the United States at the 1936 Olympic Games.

Unbreakable bonds

Most people, Brown said last week, remember the 1936 Games for Jesse Owens’ spectacular four-gold-medal performance. “That’s a great story; it re-establishes our fundamental beliefs of equality and fair play,” Brown said.

But the feat of the boys in the boat — actually, a red cedar “shell” designed and crafted by legend George Pocock — was the best story of the games, Brown said. And not just the competition, he said, but the relationships they formed over the year. The nine crew members agreed to meet once each year for decades — and did so nearly each year — until they started passing away. H. Roger Morris, the last surviving member of the U.W.’s legendary 1936 men’s crew, died July 22, 2009, at his home in Maple Valley at age 94.

The relationship Rantz formed with his teammates, Willman said, showed her father truly changed over the years.

“That sport requires the ultimate in team participation,” she said. “(But) he didn’t trust anyone. He’d been kicked around.”

Brown noted that Rantz would tear up at times in that interview six years ago.

“It was not sadness,” Brown noted, “but the beauty of it all.”