by John Maxwell

For the Sequim Gazette

Editor’s note: This is the third in a monthly series about the Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge, past and present. — MD

While the Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, it has come together like a jigsaw puzzle with pieces contributed by several other agencies and entities.

Those have included the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, U.S. Lighthouse Service and U.S. Coast Guard, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, Washington State Parks, Clallam County and local private property owners. Here is how it all came together.

To assemble a jigsaw puzzle, you first need a table. That was contributed by the First Peoples, ancestors of the Coast Salish people and the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe. They arrived 10,000 years ago after the last ice age. S’Klallam call the spit “Tsi-tsa-kwick” and the bay “Tses-kut.”

When they signed the Point-No-Point Treaty of Jan. 26, 1855, they ceded their rights to most of their land, but retained hunting and fishing rights in all the accustomed places, including Dungeness Bay. Those rights still hold today.

The first federal puzzle piece was set down in 1850 when the U.S. Lighthouse Service included Dungeness Spit on its short list of hazardous places needing a lighthouse.

On Oct. 1, 1851, the service reserved 190 acres on the spit. Funds were appropriated in 1854, but tense relations between the whites and Natives in Washington Territory delayed construction until 1857. On Dec. 14, 1857, the lamp was lit on the 100-foot tall tower.

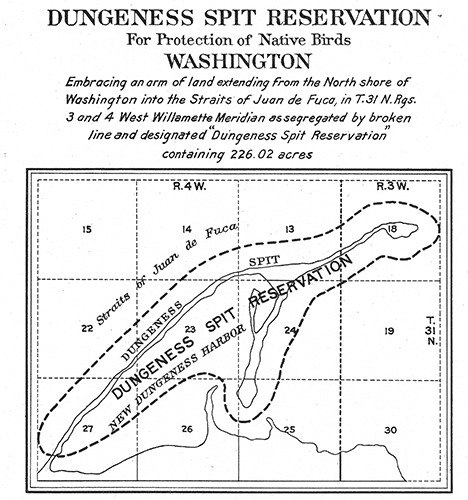

President Woodrow Wilson added the second federal piece by signing Executive Order 2128 on Jan. 20, 1915, establishing “a refuge, preserve and breeding ground for native birds” and naming it Dungeness Spit Reservation. This piece overlaid the lighthouse station and allowed for the lighthouse and any future possible military uses of the spit. In 1940, a Presidential Proclamation changed the name to “Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge.”

Piece No. 3 was joined to the puzzle temporarily from 1940-1955 when the U.S. Navy had complete authority over the spit as a military reservation. They returned it to the Fish and Wildlife Service in 1955. Meanwhile, on May 29, 1943, Washington added piece No. 4 by granting to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service a permanent easement to 321 acres of second-class tidelands within the northern portion of Dungeness Bay “for the purpose of establishing on these lands a wildlife refuge.”

That protects the eelgrass beds that are the heart of the refuge.

Washington State Parks had a small picnic park at the tip of Graveyard Spit during the 1960s, but closed it in the 1970s.

Even then the refuge still was not attached to the mainland. Over time various private lands were purchased to remedy that and to complete the puzzle. On Dec. 17, 1970, the refuge purchased from Mr. and Mrs. Haugland 45 acres consisting of the forested section and bluffs to the west of the base of the spit.

On March 23, 1972, it purchased 29 acres from Walter B. Mellus. These two sales connected the refuge to the mainland for the first time.

The purchases also included a road right-of-way that allowed the service to maintain vehicle access to the spit. On March 6, 1973, Cecil L. Dawley donated 129 acres of land on Sequim Bay straddling U.S. Highway 101, including both waterfront and upland forest.

In 1982, the U.S. Coast Guard ceded 157.5 acres of the spit to the refuge.

The current refuge administrative site of 5.04 acres was purchased from Mr. and Mrs. Krier on Nov. 20, 1996. This purchase also provided a buffer for the refuge.

Finally, The Nature Conservancy of Washington assisted the service in the purchase of the Weinstein Tract, consisting of 4.56 acres of coastal forest, on May 19, 1999.

This tract protected the viewshed to the east from the observation platforms along the main trail.

The refuge leases the public restrooms and parking lot near the entrance from Clallam County.

With 772.52 acres, the refuge puzzle is now complete. And no extra pieces left over!

Now it is our generation’s responsibility to protect the refuge and hand it on intact to the next generation.

John Maxwell is the historian for the Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge.