With the Aug. 6 primary approaching, voters who haven’t yet mailed in their ballots need to decide whether to support a levy increase for the county’s biggest employer that would more than double the amount of property tax they currently pay.

If approved, Proposition 1 would raise Olympic Medical Center’s property tax levy rate of 44 cents to 75 cents per $1,000 of assessed property value — the maximum rate allowed by state statute. It needs the support of a simple majority of voters to pass.

Clallam County Hospital District 2 — which operates as OMC —is one of 56 public hospital districts in the state. It stretches from Lake Crescent to the Jefferson County border and is the county’s largest employer.

OMC says that it needs to lift the cap on the current levy rate so that it can continue to deliver essential services to the community. Among these are round-the-clock emergency and obstetric care, and its Level III trauma center and intensive care unit.

“We’re at a point now where we have to ask and we didn’t want to ask,” OMC Chief Executive Officer Darryl Wolfe said.

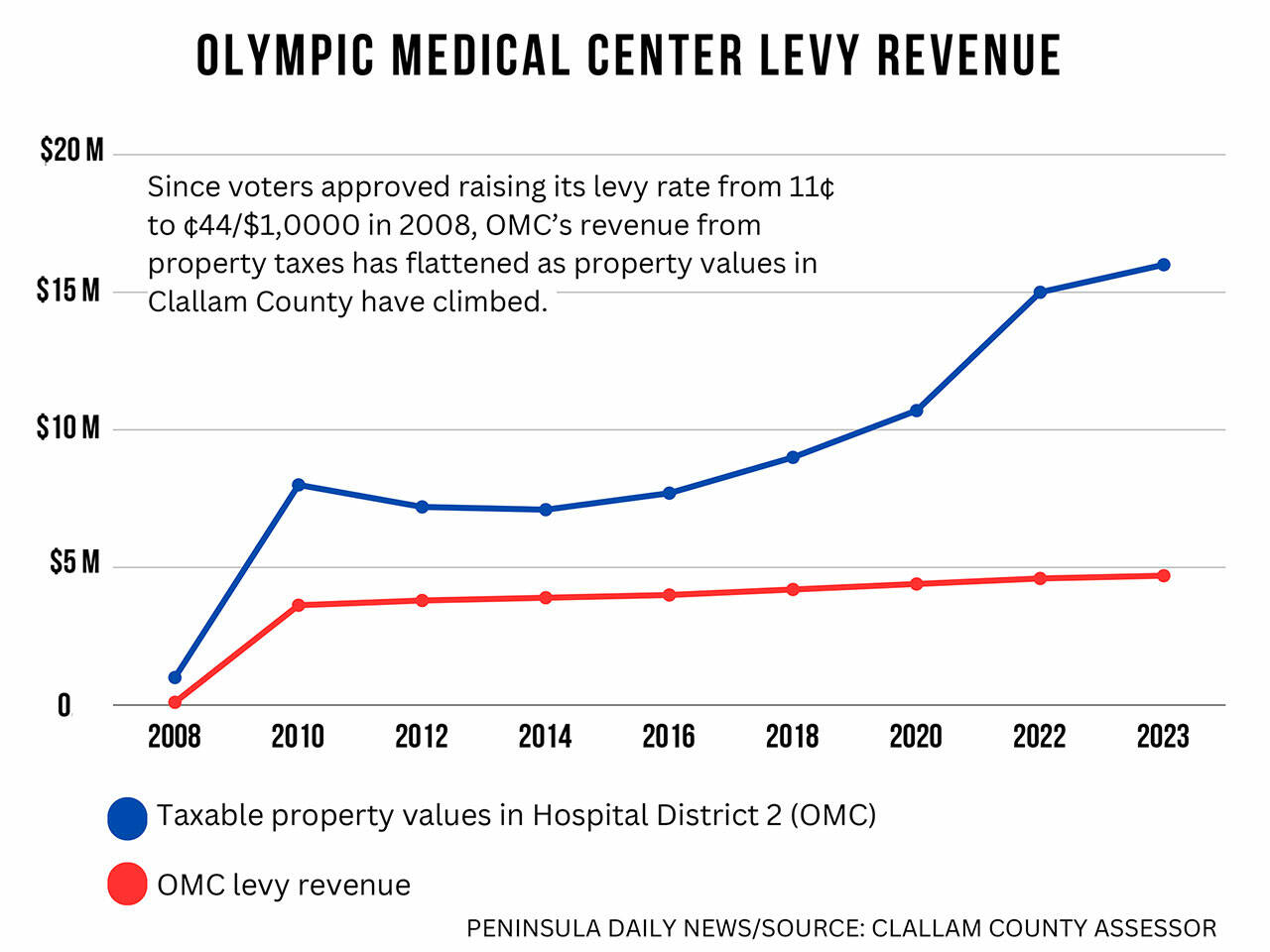

OMC doesn’t have a history of going to the community for levy increases. After the hospital opened its doors in November 1951, it took almost 60 years for it to place a measure on the ballot. That was in 2008, when voters approved quadrupling the levy rate from 11 cents per $1,000 to 44 cents per $1,000.

As property values in the county have gone up, the levy rate has fallen from 44 cents per $1,000 to 31 cents per $1,000, flattening the tax revenue OMC collects every year. The proposed 75 cent per $1,000 levy rate would also likely fluctuate with property values.

The owner of a $300,000 home who paid $93 a year in property taxes at 31 cents per $1,000 rate would pay $225 a year at the 75 cents per $1,000 rate — an increase of $132 a year or 83%.

Property taxes currently make up about 2% of OMC’s operating revenue. In 2023, for example, the levy raised $4,732,306 when its revenue was $237,796,192.

If the levy rate remains 31 cents per $1,000, OMC will collect about $5 million in 2025. Should it pass, the new rate would generate more than twice that amount — about $12 million. (These numbers are approximate because 2024 property values won’t be certified until October.)

Like 85% of the hospitals in the state, OMC is losing money: $17.7 million in 2022 and $28 million last year. While the pace of the losses has slowed, persistent issues related to poor reimbursement from government-payer programs and mounting costs for labor continue to be significant factors affecting OMC’s bottom line.

Since 2019, OMC’s revenues have increased 9% at the same time as its expenses increased 27%. Supplies and services now eat 33% of its operating revenue, compared with 27% in 2019. In 2023, OMC’s operating margin was minus 12% and it has had to dip into its cash reserves to sustain its operations.

The current situation is not sustainable, Wolfe told commissioners at the May 1 meeting at which they unanimously approved a resolution putting the levy on the August primary ballot.

“The six years prior to the pandemic we averaged a 1.9% margin as an organization. That allowed us to keep up with our salaries, continue to invest in our infrastructure, pay principal and interest on our debt and so on,” Wolfe said. “In hindsight, we were never really getting ahead, we were maintaining.”

Two years ago, OMC initiated a slate of cost-cutting measures to reduce expenses. It instituted a hiring freeze (but no layoffs), rigorously monitored overtime, restructured some of its debt and reduced redundancies and scaled back services at some of its clinics. In one year, it cut $5 million in supplies and services. It hired a consulting firm to assist it in capturing more revenue and creating efficiencies throughout the organization.

Decreasing its reliance on expensive contract labor that peaked during COVID has been a priority in reducing losses. OMC cut the number of travelers it uses by about half in 2023, although it continues to rely on them for positions where there are staffing shortages, such as registered nurses. At the same time, compensation for its permanent workforce has increased 8% per employee.

There are some factors contributing to OMC’s financial struggles, however, that are out of its control.

Unlike a private hospital, OMC can’t refuse care to anyone who comes in its doors whether the individual can pay or not. Last year uncompensated charity care cost OMC $7.5 million.

“We look across the organization and there’s lots of things where you don’t have a choice,” Wolfe said. “We don’t get to turn people [away].”

Like hospitals across the state, it can’t it discharge patients who no longer need acute care, but don’t have a safe place to go, such as a skilled nursing facility. This not only places a financial burden on OMC, but strains staff and healthcare operations.

OMC’s most intractable challenge in turning around its financial situation, Wolfe and its board of commissioners have said, is OMC’s payor mix that is increasingly weighted toward state and federal insurers. About 85% of OMC’s patients are on Medicare and Medicaid, which pay about 80% of the cost of care — leaving OMC to pay the difference.

The hospital has been working with Washington’s Congressional delegation on increasing reimbursements and pressing the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for change. Although Medicare is expected to increase reimbursements by 3.1% this year, the $12 million bump to OMC’s bottom line will not solve its fiscal troubles.

“At the end of the day, our fundamental problem is that we are funded by government programs that don’t pay the cost of care,” Commissioner John Nutter said on May 15. “There is no way we can cut costs enough to live within what we get paid.”

Since 2022, 64% of hospital levies have passed, according to the Association of Washington Public Hospital Districts. Forks voters in February approved increasing Forks Community Hospital’s levy rate from 39 cents per $1,000 to 75 cents per $1,000 — the same OMC is asking.

If the levy doesn’t pass, OMC will need to make some difficult decisions, Wolfe said. One would be eliminating some services and the other creating partnerships with other health systems like Swedish to cover the gaps in care that it would be created by cutbacks.

The levy alone would not solve OMC’s financial crisis, Wolfe said, but was an important piece of an overall plan for stabilizing its financial footing.

“It doesn’t fix everything,” he said. “But it’s a it’s a huge help to us.”