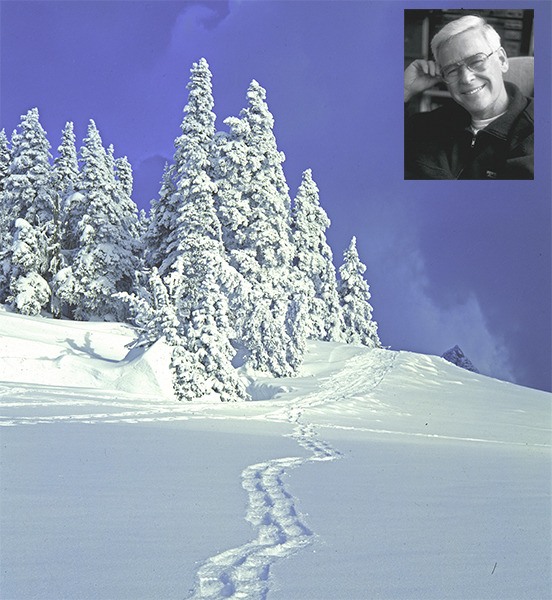

“I don’t ever remember a boring day in the Olympics,” Ross Hamilton said from the comfort of a modest lounge chair in his home located in the heart of Sequim.

Many men in their 70s may be happy or even delighted to sit comfortably in the middle of town with nearly all modern conveniences at their fingertips, but if Hamilton had it his way, he’d be in a remote setting, tucked away in the foothills of the Olympic Mountains with only nature as his companion.

Instead, Hamilton, a prestigious and widely recognized landscape photographer of the Olympic Peninsula, has had to adjust to a lifestyle surrounded by people after the ongoing loss of his ability to see.

By 2000, Hamilton admits he’d lost his vision due to glaucoma.

However, prior to the loss of his vision and for more than 40 years he captured some of the most naturally beautiful sights any eyes could see. He spent a lifetime documenting timeless images of the area’s local beauty for countless minds to get a glimpse into what his eyes once saw.

Differing from digital, Hamilton perfected the craft of photography using 4×5 and 35mm film cameras, instilling in him the importance of being selective and mindful of each photograph.

“At the top of my game it took me about a half hour to take a picture,” he said.

The many hours he spent watching the light of day twist and turn, waiting for an opportunity to photograph something maybe worthy of the landscape’s beauty, equate to many days spent in the Olympic Mountains, Pacific Northwest coastlines and all the spaces in between. “It’s taken me 40 years to get to know this place … it’s depth and diversity,” he said.

Hamilton’s intrinsic love for the outdoors, solitude and wilderness began as a child. Although his father was born in Sequim, Hamilton grew up in Burbank, Calif., until he was 26 years old. Growing up among thousands of people, in a sprawling area primarily covered in concrete, he developed a “deep hunger for quiet places and wilderness,” he said.

Hamilton attributes his early appreciation and passion for the outdoors to his parents, who placed a lot of value on being outside and in nature during their family trips, as well as supporting him through Boy Scouts.

Also, he can trace his first exposure to photography back to his parents.

“When I was 9, they gave me a black and white camera and I remember I found it to be an easy tool to use, or should I say toy to play with,” he said.

Throughout his childhood Hamilton’s interest in photography developed and always seemed to revolve around scenery and landscape photography. During this developing love affair with the craft of photography, he grew to prefer large format.

If his interest in photography ever wavered, the summer of 1966 confirmed Hamilton’s passion while working with renown photographer Ansel Adams at Adams’s studio in Yosemite.

“That’s where my education really took off,” he said. “I was exposed to his (Adams’) world and I’ve never looked back.”

With pure confidence, Hamilton easily admits “that was the happiest summer of my life.”

By the 1970s, Hamilton had purchased the equipment needed to seriously pursue photography, however, recognizing most successful photographers also were wise businessmen, he studied business. After earning his master’s degree at the University of California – Los Angeles, he headed north, leaving behind the dense cityscape.

Hamilton can vividly picture the first time he saw the Olympic Mountains.

“I came over the top of the hill in Shelton and saw those mountains and said, ‘Yes, this is where I belong,’” he said.

From then on, the Olympic Peninsula with its snow-capped mountain peaks, sparse alpine forests, densely covered temperate rain forests and meandering river valleys, to wind-beaten coastline, became Hamilton’s alphabet, his language — his most raw form of communication.

“I don’t do photography for myself, but I want to share the story I’ve enjoyed with others and photography is the closet I’ve gotten to being able to do that,” he said. “It’s my form of communication because I’ve always said that ‘I don’t talk good.’”

In photographing the Olympic Peninsula, Hamilton said he had the “whole gamut” when it came to variety of landscapes.

“Within a 50-mile stretch the variety and diversity is extraordinary,” he said.

Having traveled to many parts of Canada and Europe, Hamilton still considers the Olympic Peninsula and Olympic National Park one of the most “unique” places.

One subject Hamilton especially enjoyed photographing and simply admiring, or getting lost in its lore was Mount Olympus — the tallest mountain in the Olympic Mountain range. Dotted with nine glaciers, the mountain attracts a range of personalities. For Hamilton, he found himself revisiting the mountain to observe it and do his best to capture its presence on film, but notes many visited Mount Olympus and continue to do so with shear determination to climb it.

“I think generally photographers are observers,” he said, noting the pure “grandeur” of mountains and the views they offer.

“What is it about us humans that want to see so far?” he asked himself while revising his memories of Mount Olympus.

The days Hamilton had in the far reaches and backcountry of Olympic National Park and surrounding wilderness were some of his fondest times. “Being able to watch a day move from morning, afternoon to evening was a luxury,” he said.

As he waited for a desired light given “the lighting could make or break a photo,” Hamilton experienced some of the world’s more subtle, yet to him, priceless moments, like the opportunity to see marmots dance. With a smile stretched across his face, Hamilton described being able to witness two marmots come together, lock paws and seemingly dance.

“Those are the awards of sitting still and watching the world go by,” he said.

Hamilton’s heart was always outdoors, dancing with the marmots, but to supplement and help support his life as a photographer, he spent 25 years working in retail.

Without today’s digital advancements, landscape photography was and remains one of the most difficult forms of photography because of the many uncontrollable variables, like lighting, Hamilton explained.

“When you think it’s stationary, everything, even a meadow or stand of trees is in a state of motion,” he said.

The rate of change offered by the Olympic Mountains and surrounding area helped draw Hamilton in and challenge him, but that same unpredictability was why Adams admittedly didn’t like the Olympics, he said.

Like the constant changes within a forests, Hamilton has spent the past 15 years of his life changing and adapting to life without eyesight — the very sense that allowed him to express him and share his story.

“You learn to adapt,” he said.

Without his vision, he’s become more reliant on his other senses and memory, such as knowing the number of steps from his front door to the neighboring house.

The most “interesting” outcome of his diminished vision is that it has forced him to interact and rely more heavily on people, he said. “By nature I’m a recluse, but I’ve learned to really appreciate and love people and their beauty,” he said.

When asked whether he misses being able to see the vast, outstretched landscapes that were once the canvas of his art, Hamilton uses the word “grief” as perhaps the best way to describe his inability to see once more all the familiar places where he found the most beauty and peace.

Although the loss of his vision limited his ability to work out in the field, let alone spend day after day in the backcountry, it also led him to shift his attention toward a book and for the past 12 years he’s drawn from his collection to create calendars.

With the help of a friend and sales representative Sandy Frankfurth, a dozen of Hamilton’s timeless photographs are handpicked each year. The process takes about three months, he said.

“We try to be sensitive to the season and to give a nice variety of subject matters,” Frankfurth said.

The recently released 2016 calendar includes some of Hamilton’s unseen images, including one of Lake Margaret nested deep within the Elwha Valley and the picturesque, yet no longer Lake Aldwell.

All the images used for the calendar are accompanied by an inspirational or thought provoking quote, as well as local tips and seasonal suggestions.

The image for October is joined by a quote from an unknown source, but simply states, “Where a beautiful soul has traveled, beautiful memories remain forever” — much like those eternally captured in Hamilton’s mind’s eye.

For more information on Hamilton, visit www.rosshamiltonphotography.com. Calendars are available in most local retail outlets and book stores.

Reach Alana Linderoth at alinderoth@sequimgazette.com.