Have you ever stood on the smooth top of a glacier? Heli-skiing perhaps? Or maybe you were deposited there by bus during an Alaskan cruise?

If you’re a scientist working for Olympic National Park, you probably skied there. Sound fun?

It does to me.

Officially, Bill Baccus is a Physical Scientist with Olympic National Park. But the tall, lanky outdoorsman is well known for his tenacious ski mountaineering in the name of science. Baccus has skied and scaled many peaks and glaciers in the Park in his three decades living in Port Angeles, collecting data from remote weather stations and measuring snow depth.

If the photos on his employer’s website indicate one thing, it’s that blue sky against snowy glaciers makes for a lovely office.

While Bill has had a physically active and picturesque career, it would be over-romanticizing to say it’s been all fun. The long-term field data he has helped collect tell a brutally honest story of change and loss.

The glaciers he visits are radically smaller and fewer, and winters are warmer, than when Park scientists started taking measurements.

What the data show

“Our park has lost 82 glaciers since 1984,” according to Bill. “There were eight valley glaciers when the park first inventoried its glaciers in 1958, and now just four of these have ice extending down into their lower valleys.”

I’ve seen Bill’s large data tables and graphs with downward-sloping trend lines. The story they tell is alarming, to be sure.

But what really hits me in the gut are the photos.

Sad – and scared

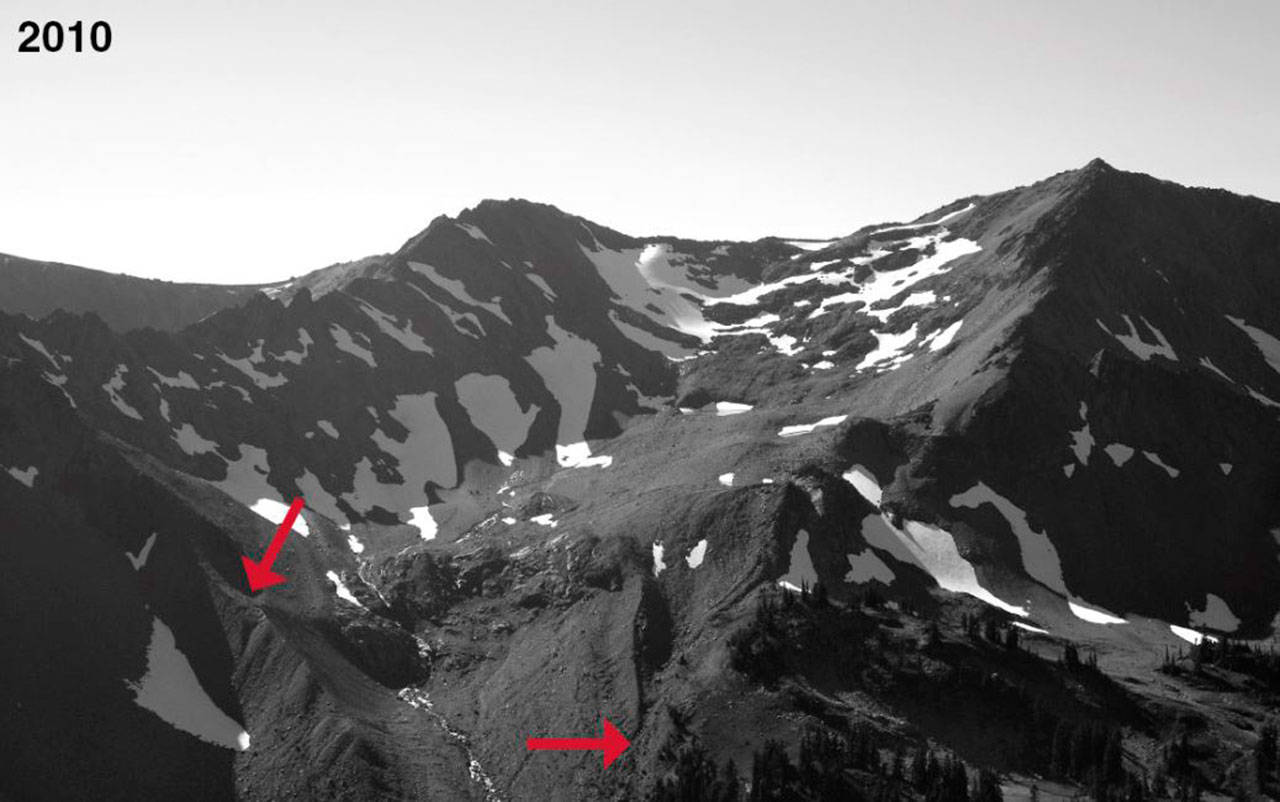

Three weeks ago, toward the end of my talk kicking off the “Story of Water: In Depth” lecture series, I showed one photo of the Lillian Glacier in 2010, taken by Olympic National Park. The rounded basin created by that glacier is called a cirque, and it forms the ridge at the very top of the Dungeness Watershed.

The cirque is empty. Lillian Glacier is all but gone.

After my presentation a woman approached me with a technical question about treating tap water but before she could articulate the question her eyes suddenly brimmed with tears and she shook her head, saying, “It’s so awful about that glacier!”

She was sucker punched, and I didn’t have anything to comfort her.

Our annual dose of melted snow and ice providing stream water and aquifer recharge is greatly compromised by climate change and, in the Dungeness, it is probably too late to reverse that trend. The cost of adjusting to new management methods and preserving summer streamflow looms large.

A great presenter

Bill Baccus is disarmingly gregarious, even while delivering brutally honest news about glaciers. In 2015, the worst year for snow in the state’s history, Bill observed, “It’s been a bad year if you’re a glacier.”

He has no reason to second guess or beat around the bush because the data and photos are very clear: the water stored in Olympic Mountain glaciers that has filled our streams when the weather turns warm each year is radically reduced.

Bill is a great messenger despite a difficult message. I highly recommend coming to hear him present tonight, November 13, 6:30 p.m. at Sequim Civic Center, 152 W. Cedar St. For more information, check out www.lwvcla.org/story-water.

Geek moment

For newsletters on the climate, subscribe to updates from these governmental, academic and local institutions, respectively: www.noaa.gov/climate, www.globalchange.gov, www.cig.uw.edu and olyclimate.org.

From the vantage point of my office I look at the rugged ridge at the top of our watershed this time of year and watch the peaks go from brown to white. Looking beyond the ridge to the sky: what will it bring this month? Normally our wettest month of the year, November started out slow. Our recent rain is a good thing, but snow in the mountains is even better.

‘Tis the season for a snow dance.

For the 2020 Water Year (started Oct. 1):

• Snow accumulation at the Dungeness SNOTEL station, elev. 4,010 feet: 0 inches (normal for this date); Lowest minimum temperature = 38 degrees F.

• Rain in Sequim through Nov. 10 at the Sequim 2E weather station (sea level): Total rainfall = 1.8 inches; High temp. = 60 degrees F on several dates; Low = 22 degrees F on Nov. 1.

• River flow at the USGS gage on the Dungeness River (Mile 11.2): High = 873 cubic feet per second (cfs) on Oct. 22; Low= 113 cfs on Oct. 15. Range for the past month 115-900 cfs.

• Flow at Bell Creek entering Carrie Blake Park: none; Bell Creek near the mouth, at Washington Harbor: autumn flow generally 2-4 cfs.

Ann Soule is a hydrogeologist immersed in the Dungeness watershed since 1990, now Resource Manager for City of Sequim. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent policies of her employer. Reach Ann at columnists@sequimgazette.com or via her blog at watercolumnsite.wordpress.com.